Closer to Home

November 24, 2013 / Remembering November 22, 1963

I was 25 years old on November 22, 1963.

Eleven years before, our junior high school class had learned all about the government. We learned about its three branches, the concept of checks and balances among them, the requirements for being a Representative, a Senator, the President. We learned some obscure words—cloture, lame duck, filibuster, quorum. Dwight David Eisenhower had just been elected (an elderly bald fellow), and we all memorized and were tested on the names and jobs of everybody in his Cabinet.

We also had to memorize and recite, each of us in turn, the Preamble to the Constitution, and had to know at least a paraphrased version of the Bill of Rights. I guess I didn’t much think of this as MY Bill of Rights.

I didn’t know much, really, you know. “Politics” was a thing that boring old men did.

Then Jack Kennedy came on the scene. By then I was old enough, and perhaps a little bit smarter, to recognize him. To recognize his glow and sparkle. He said stuff I could understand, that seemed interesting and important, at least in the way he said it. His wife—not granny Mamie Eisenhower for sure--was only nine years older than I, imagine that! They were both smart, and radiant.

I was working in New York City at the time, and one noon-time Jack, campaigning for President, came through the garment district, near my office, and I went over to see the motorcade. A snow of paper and fabric scraps fluttered down on him, almost obscuring my view. As he passed by, smiling that inviting smile, the crowd pressed forward and actually carried me off my feet for an instant. It was scary, but I was elated to have seen him.

To my everlasting shame, though, I didn’t yet know much after all. For I let my then-husband talk me into voting for the other person.

Still, In January, on Inauguration Day, an office-mate and I spent our lunch break in a nearby bar, eating bacon and peanut butter sandwiches and watching a little black-and-white tv behind the bar. The great cadences of the Inaugural Address, and the meanings borne by them, astounded and thrilled me, unformed person that I was.

So I finally started reading newspapers, to see what this new, interesting president said and did. Dimly I began to perceive a larger world. You will think I was remarkably stupid—at my mature age of mid-twenties—but it was a different time.

In the fall of 1962 we got through the Cuban Missile Crisis—or President Kennedy got us through it. The headlines were terrifying: OFFENSIVE MISSILE SITES ON CUBA ROCKETS POINT TO U.S. ALL AMERICAS IN RANGE KENNEDY BLOCKADES CUBA KENNEDY READY FOR SOVIET SHOWDOWN Those of you not old enough to remember the Cold War will be disconcerted to learn that in junior high school I had not thought I would live to grow up, that sooner rather than later we would all be bombed into death. That’s the kind of world it was then.

My parents had been going to come from Denver for Thanksgiving (by then I was living in Cambridge, Massachusetts). About halfway through the thirteen days of the Cuban-Soviet-U. S. confrontation I called them; did they think maybe they should come sooner? That’s how we were thinking. But then his cool head and clear thinking prevailed (that is how I perceived things), and life went on. I watched his deft, brilliant news conferences, and was proud of him, my President, and proud of my country which chose him.

Oh, but then, but then…

A Friday. I went home from work for my lunch hour. I came back to the office. I walked in. “You haven’t heard! You don’t know!!” they cried.

“What? What is it?”

“The President has been shot, in Dallas!”

A colleague and I ran out into the parking lot to listen to the radio in her car. We sat in the front seat, both doors open. At the moment of the announcement of President Kennedy’s death, a young boy, perhaps 13, walked across the parking lot. He looked over and saw two adult women weeping. I am sure we are a part of his memories of that horrible, horrible day.

Everyone left the office. I wandered around Harvard Square, weeping. It was chilly and gray. “Did you hear? Do you know?” everyone asked each other, just as I remember my Mother doing the day President Roosevelt died, as she walked me, aged 6, home from school.

That terrible November day, my tiny black and white television went on and stayed on for three days, all day and all night. We were there in virtual presence with the countless thousands of mourners filing past the coffin in the Capitol. The television cameras just stood there, being our eyes, and not a word was uttered nor needed to be uttered during the long night of mourning. We stood in virtual attendance as the funeral procession marched by in the morning, the saddest sounds and sights I hope I ever hear and see. We saw Mrs. Kennedy, noble in her widow’s weeds, accompanied by the heartbroken brothers of the President. We saw the fatherless little children on the steps of the church. We were there at the burial, saw the crisp, heart-breaking finality of the flag-folding.

And yes, I saw Ruby kill Oswald, as I was standing at the sink in my tiny kitchen and looking over at the tv.

So all of that happened fifty years ago. Ancient history to, say, my grandsons. Rather like the First World War was to me, when I was their age.

Here in Massachusetts, we claim the Kennedys as our own. And on this 50th anniversary of the President’s murder, I thought it proper to visit the Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, on the edge of Boston Harbor, to pay my respects and to bear witness.

I am good at waiting for things I want to do, and so I got to the Library very early, an hour or more before opening time. It was raining lightly, and a small group was already gathered in an entryway. Perhaps a dozen of us shared our Kennedy stories; no one was as old as me, and they listened carefully to what I have related above. The first person in line was a young girl from Schenectady. Other people were from South Dakota, Chicago, and even Ireland.

The line got longer, people standing under their umbrellas and sharing their stories. The press was there, and some of us were interviewed. Then the door opened, and we entered.

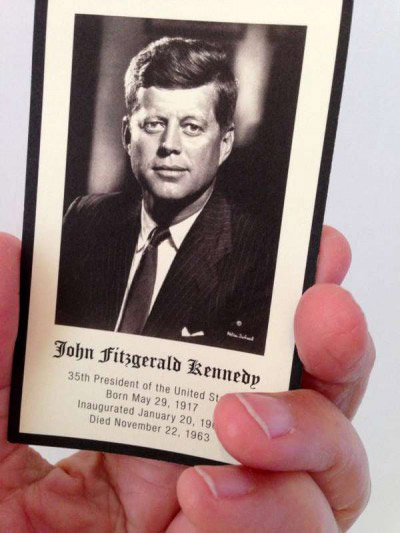

A gracious staff person, dressed in black, handed me a small copy of the Mass Card designed by Jacqueline Kennedy and distributed at the funeral. It has a fine portrait of the President, and his dates. Thus came the first of my tears that day. Small boxes of tissues were placed discreetly here and there, and I made use of one.

Guest books, each flanked by white roses and a portrait of the President, were available for signing. People lined up in front of them.

A room was devoted to the funeral. People watched film of it somberly, in deep silence, except for the dreadful cadence of the drum beats. There was the saddle with the boots reversed in the stirrups, carried by Black Jack, the spirited horse representing a fallen warrior. And there was that flag, the folded flag from the casket. I looked at all of these things.

People passed slowly through all the exhibits, paying particularly intent attention, I thought, to films of the President speaking, as if taking in his demeanor, his words, their meaning.

There was to be a memorial tribute, with music and spoken words, and we all went to a large hall to view it on the screen. I went in early, and waited. A wall of windows at the front of the hall looked out on a foggy harbor, a plain view which seemed appropriate on a day of mourning.

We all watched and listened to the playing and singing, and to people reciting some of President Kennedy’s words. We observed a minute of silence at the time when his death was announced. We heard the governor of Massachusetts repeat: “And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

Yes, mourning, not so much for a person as for a state of mind, that delight and hopefulness, which rose so suddenly and was so suddenly destroyed.

Things never were the same, after the assassination.

Comments

-

Jeremy Murphy 04:06pm, 12/12/2013

That is the most beautiful tribute to President Kennedy that I’ve real all year. Thanks for sharing your memories. I also went to the JFK Library that day to remember his life and legacy. We shall not see his like again.