June 9 - 21 1990 / A Ukrainian Sees America 1990: Gifts of the Prisoner

Slavko, My Ukrainian Cousin, Comes For a Cruelly-Short Visit in 1990

Part 1 - Slavko Arrives

A Note About This Journal

In light of the on-going events in Ukraine, I decided to post this journal. I am half Ukrainian; my late Mother was born there and although she came to America with her family at a very young age, and was a proud American, she also remained a fervent Ukrainian patriot throughout her life. With her, I visited Ukraine three times, the first being in 1963 (the very dark ages), again in 1976, and again in 1985. On the first two visits came the joy of meeting our extensive family there, including my cousin, Slavko. Never in a million years did we ever think any of the family would be allowed to come out of the USSR to visit us. But travel restrictions were somewhat lifted by 1990, and Slavko came to America, first to visit my Mother in Colorado, and then for the visit to me and my family described herein.

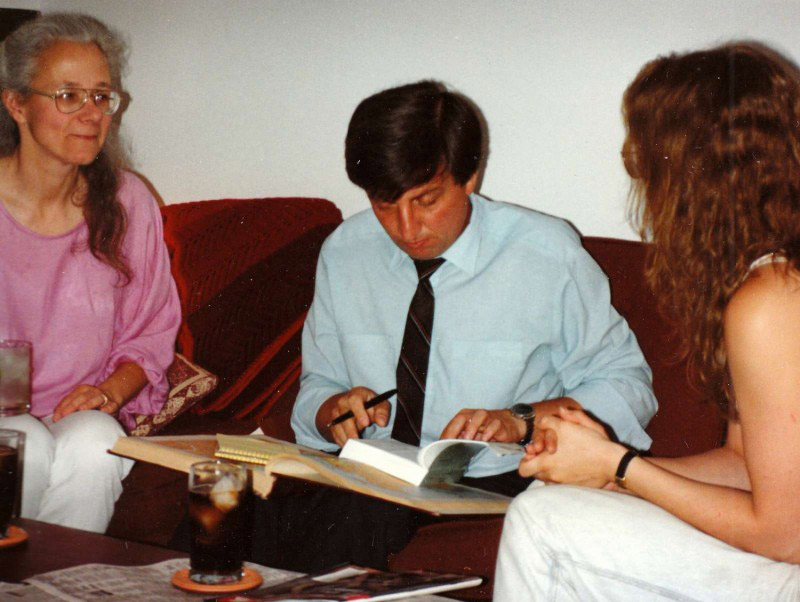

I have only a few images of that visit, and those only as prints. Marvelous technology has made it possible to include a few of them with this journal entry, but there are neither thumbnail images nor a Picasa gallery with it, as there are for my other travel journals.

Since 1990 we have lost contact with Slavko and his family; my Mother has passed on and I neither write nor speak Ukrainian, so sad… But Slavko’s indomitable spirit shines bright in the memories of my own family, and we love him and wish him, and all of his countrymen, well. I hope that you are moved by reading this account of his visit to America.

--Hilary

Slavko's been back home in Ukraine for a day, or two days maybe, by now. The pile of goods from America--clothes and electronics--that assumed such immense importance, carried so much weight in the packing and the carrying home, bringing home, has begun to diminish in luster, almost imperceptibly. There are tiny bitter disappointments among the recipients (the navy blue suit is too large and will be very difficult to alter, the jeans skirt is too tight, the slip too long, someone at work got a boom box that was better in some way, she hoped for some precious green embroidery thread too, and the design on the ties is for women's things), followed by hasty thrustings away of such ungrateful thoughts. The pile that loomed so large, as tokens of the journey to America, that I packed with such care and love, that he carried with such anxiety and fierce protectiveness, has begun to assume its proper size.

For it's clear that it's what's in the head, behind the eyes, in the heart, that will become the myth. Already the memories and ideas have begun to slip into their permanent places, in the first, the second, the many retellings. "I want to give you," I dictionaried laboriously, "memories to fill your heart and your eyes." "I have memories to fill a lifetime," he worded back.

For the things, are, after all, only objects, material gifts. They will soon assume their proper places as signs and tokens. But the intangible profoundly human gifts of memory and feeling, imagination and idea, take root in the soul and eye and do not fade but instead are nourished in a rich life of their own, grow and prosper in the climate of the mind and heart, and enrich the dreamer, fill the dreamer with good things, the fruit of daring. Fruit to feed a lifetime, and lifetimes beyond in the minds and visions of others with whom the dreamer has shared.

Time after time Slavko signified in gesture how filled with idea and feeling he was. The invisible weight of emotion and thought, carried home as surely as the objects in his suitcase.

So in the end, then, he can have it all, in his mind and mind's eye. The gift of the prisoner, to see beyond the walls.

Saturday, 9 June 1990

The guest bedroom is ready, books of photographs of America on the bedside table, nice new bars of pink soap, soft pink toilet paper and Kleenex in the bathroom. The small two-way dictionary, bought that morning, is at hand. The family gathers for the trip to the airport. Will we recognize him? Has he changed? Has he gotten, well, stuffy? From our family trip to Ukraine we all remember a lively, warm, competent person. A person with dreams and ambitions that seemed beyond realizing in 1976, when last we saw him. Now brought to us by the winds of change and the power of his own dream.

We arrive early, nervously pace around, coffee, donuts, waiting. I think how he will be enjoying this flight, alone in America at last, after his two weeks in Denver with Mother, able finally to pretend he is an American, try that on, try that out, released from dependency for a few hours, making his own way as a grownup man. I feel his anxiety. Will we be stuffy? Distant? Will he be able to communicate? Will he be able to accomplish all that he desires and yearns for from this trip, or will there be bitter disappointments, after all the terrible labor and determination, because he must be dependent on us and cannot make things happen as he needs, as he might at home?

It's landed! It's landed! There it comes! Which way are they coming out? We flick our anxious glances over each emerging traveler, not quite knowing who we are looking for. Soviets have that awful pasty, pale, rumpled look to them. He's tall, we know, but he'll look unmistakably Soviet. I have that hollow feeling in my stomach of the excitement of meeting.

There he is! It's him! We cry out in delight and clap our hands in joyful excitement: he did it! We did it! He's really here! He's really here with us! This tall smiling tanned brown-haired man breaks into an energetic trot the last few steps and into my arms for a close embrace that dismisses words, distance, time, nations. Oh, you are welcome here, you are surely welcome here.

He embraces John, Alyson, Susannah, and is introduced to his cousin Olga and her friend. All talking at once, we go downstairs for Slavko's bag, a long time in coming but we don't care. Olga talks with him in Ukrainian and the rest of us try to follow the conversation. But mostly I just enjoy looking at him. He does not seem to have aged in the slightest since I saw him last, trotting on the other side of a fence at the airport in Lviv, trying to follow to the last minute our bus out to the plane as we gazed at each other a last time in tears. An image as clear now as it was when it imprinted itself painfully on my eyes.

Standing and waiting impatiently at the baggage carousel, I begin immediately to see my country through another's eyes. Why must it be this time that the bags are so late? For the next twelve days I am afflicted with this double vision; things I normally tolerate without question or with a mental shrug leap out at me in unpleasant clarity. I apologize to Slavko with an irritated gesture for the delay, but he looks unflustered. Finally the large vinyl bag comes. It's clearly new, and clearly junk. I imagine perhaps his wife Maria buying it for him, or he himself standing several hours in line to get it. I imagine Maria and teenage daughter Natalya standing around helping him pack it. I imagine them imagining him here now. Following his progress with anxious pride. John and I imagined him on his way here, how his family and co-workers would have sent him off festively and enviously.

The seven of us crowd into our car. Olga and Slavko are talking, but we don't get much of the conversation.

At home, I show him his room, begin to demonstrate the workings of the convertible couch. Oh, I understand, he says. It occurs to me later that probably he and Maria sleep on a similar bed. As we take him through our beautiful new house, he is awed, shakes his head, says how beautiful it is. At home, he says, there are the three of them in two rooms. I show him his bathroom. I am delighted to be able to have a bathroom just for a guest. I introduce him to Tiger cat, who is less than enthusiastic of course.

Supper is spaghetti, though I am so flustered by having three guests that I hardly taste it. I have laid in a supply of Coke for him; I ask him what he wants to drink, and he says Pepsi (I realize a little later that's because that's the cola that they have there), and he clearly doesn't know Coke. But he drinks it down anyhow. He is a fine guest, very much at ease, taking what comes, seemingly comfortable with whatever turns up. The kind of guest that lets the host relax. When I bring out the toppings for the vanilla ice cream, he asks to try all of them. I'm delighted.

Susannah finds that the Ukrainian she learned in earlier years is returning to her; she is actually able to converse in a halting fashion. It's those all-important prepositions and declensions! John takes pictures of all of us trying to communicate with each other, through gesture, dictionary, facial expression--wonderful pictures.

It's agreed that he will go out later in the evening with all of them--Zan, Als, Olga, and Olga's friend to the lounge at the top of the Hyatt on the river. I try to think how I would feel about this myself, if the tables were turned. I gesture if he is tired. He gestures back, Oh no!

John washes up the dishes and Slavko goes into his room and closes the door. He's in there a long time and I wonder if he is taking a nap. Eventually I tap on the door and call his name; he answers cheerfully and opens the door, and invites us all in. Arrayed around the room are gifts, an artistically arranged pile for each of us. Embroidery, wooden bowls and boxes, a bottle of something alcoholic for John, a large china figurine. I am overwhelmed that he has chosen, bought, and carried these special things all the way here for us. I realize that he will have brought things for Mother, too, and that he must have carried along very little in that big suitcase for his own needs. There are two beautiful linen tablecloths. He must have spent a great deal of money on these gifts...

...so as not to arrive empty-handed and completely dependent. He has some American money, about $300, and he has particular things he must get with it. For the family, the only evidence of this great journey he will have taken. Also, the electronic things he wishes to buy, kind of insurance against the times he feels are coming, times of civil war and even greater hardship than they now encounter. This is his way of taking care of his family, to have these goods which can be converted into money.

But he brings gifts to us, the best he can buy.

They let them come to America for a month, but allow them to bring less than $300. I am not sure where he has gotten the money he has, for some of it is in American Express travelers' checks, and some of it is cash. In any case, there is certainly not enough of it to live on for a month. So they maliciously force them to be dependent upon their American hosts, reducing them to a childlike and humiliating, emasculating dependency.

So he brings gifts to us, the best he can imagine and buy. The gifts assume a meaning far beyond their immediate presence. They are a greeting to us from the family (for the embroidery has been made by Maria), a way for those who could not come to share nevertheless, in imagination, in this journey.

Tokens.

This whole visit is a token, a fragment, a symbol, of what normal human intercourse should be. We--Mother, Slavko, Slavko's family, John and I, Susannah, Alyson, the people in the street--we are the representatives for all captive and abused people everywhere.

So the young people go out, and John and I fall into bed. I can hardly sleep. It is as if I had captured some fantastically exotic animal on my deck, and it will be there in the morning.

Sunday 10 June 1990

I'm not sure what kind of appetite Slavko has. I offer orange juice, coffee, an array of little boxes of cereals, English muffins--he tries them all. Doesn't say anything about any of them.

All during the visit, John and I notice that he eats everything, without comment. We get the sense of someone for whom eating is a chancy business; being fussy or even very discerning about food is risky. If there is food on the plate, better eat it, since it's not always clear what might be there another time. When we go into the stores, over and over again he is sobered and even grim in the face of the vast array of foods available. Here are thirty kinds of cheese; at home, he dictionaries, we have one kind--if we have it.

I invite him for a walk around the neighborhood. We carry the dictionary, or rather, he carries it. In gentlemanly and protective fashion, he saves me from labor. I like that, from him.

He sounds out the street signs. I am surprised at how well he does with this. I show him where we go on the map. We walk slowly. I like not being able to talk very much, for it frees the eyes. I tell him the approximate prices of the houses we go by. One neighborhood is black, one integrated, and I tell him that. I explain how much John and I earn. It's difficult of course because rubles and dollars are not truly comparable.

I take him to the little row of yuppie stores nearby, and buy a bag of half a dozen marguerites. Everyone in the store is very pleasant and polite, and my second set of eyes sees this. At first he demurs, frowning a little, gesturing no, never mind, about the cookies, but I indicate ”I want them” (which I do, they are fabulous) and we continue our walk, eating marguerites dusted with powdered sugar out of the bag, companionably.

I take him to our old apartment, for which I still have the key since we will not close the sale of it until next week. He understands all about this and our new house. Mother must have told him, and I am glad, for it would be a complicated thing to dictionary. When I open the door, and we walk in that lovely empty space, his face is a study. He just shakes his head. I feel that he understands the meaning of an apartment more fully than a house.

Along the uneven red brick sidewalk again, the trash is out for the trash truck the next morning. I explain this, not wanting Slavko to think we just strew the stuff around. As we stroll along, he suddenly stops dead in his tracks, for there on the top of a pile of discarded newspapers is a sleek black tuner. He's transfixed. Clearly he wants to take it. Hastily I dictionary: broken. He looks unconvinced but I try to be sure he understands. He laughs unbelievingly and makes an endearing pantomime: At home, we'd pick it up, tuck it under our arm, and hustle off gleefully. It's one of the signals that will enter our tiny gestural lexicon during this time together.

As we walk back to our house, I make a change in the talking. I tell him about Alyson and her illness of the mind. He knows, he understands, Mother has told him. I feel the tenderness of his response, how moved he is by my telling. I see just a little bit into him, past the processing of the passing scene, and into the person.

At home I prepare a very American dinner, shake and bake chicken and potato salad, and Entenmann's chocolate cake. After discovering that Olga would not be able to be at this family dinner as translator, I have spent a lot of time on the phone, trying to find someone who could be hired to translate, just this one time, completely and competently so we can exchange information and questions freely. The translator arrives: wonderful, it's Zan's former Ukrainian conversation teacher from the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute! She is superb. Although she has a clear personality, she simply translates, briskly, with expression, virtually simultaneously.

Around the dinner table, the talk goes back and forth. Slavko clearly has many things he wants to tell us, about the political situation at home, about his fears of civil war, about Gorbachev. But I am not very interested in this. I register: Yes, all that I read in the papers and magazines is true, and that's about the extent of my interest. Later on I will tell people, you can feel assured in believing what you read. That is a useful thing to know. I tell people, Oh yes, there have been many changes, good ones, but the process of change for the society, which will take a long time, grinds the individual as it happens and makes things worse in some ways, rather than better.

But my interest, as always, is in the person. And I have some important things I need to ask and tell, to set my mind at ease about the plans I have made. So I ask the translator to explain the schedule, that we will be going to New York by train tomorrow, will stay with Aunt Olga, and are there things in New York he would like to see? His response is the same throughout our time together: anything. I understand this; he is fully alert to all around him, as I am when traveling in a strange place, and all, as John always says, is grist for his mill. OK, that's settled. Then I need to let him know that we understand the things he needs to purchase, and that we will help him do this, both financially and in giving advice, and that we'll do this next weekend. It is very important to me that he know that we understand these needs. I don't want his good manners to interfere with the accomplishment of the tasks he has. Once I have reassured myself that all this is understood, I feel better.

Then I ask him what things he would like to bring home for the family, Maria, Natalya, and Mama (Natasha who I remember with such delight, a playful, vigorous, alert, and lively woman who took me out shopping one afternoon--the tablecloth she bought me I still use on the most festive occasions. I wish, I wish I had thought to show it to Slavko and tell him that to tell her). I get a pad and pencil and make a list of the things he would like to get: jeans things, a suit, "elegant," for Maria, woolen paisley scarf for Mama--and for you? I ask. Hesitantly he allows as how he would like jeans and a jean jacket, too. I am delighted. I love to shop!! The translator gives me some advice about where to get the wool scarf, since I know just what he is looking for and also know that no regular stores would have such a thing. We discuss the VCR he needs; the configuration of it of course must be compatible, and there is some talk back and forth with John about that.

As the dessert and coffee are served and finished, I realize that the translator is tiring. I have one more need of her services: that we should each tell Slavko what we do for work, a little of our places in life. John begins, explains a bit about his complicated work. He tells his salary and Slavko is amazed. It's so hard to get it all straight though--what different things cost. Then I tell, mine being kind of hard to explain also, just the idea that I work for myself and make a living that way must be a bit difficult to grasp, plus the fact that my income is so variable. Next Susannah tells her history since high school: major in math, Peace Corps in Nepal, as best she can how it was there, her computer work at the Harvard Smithsonian Observatory, and now her work as house manager at the alcohol treatment residence, and in the fall, to university for international studies.

I am suddenly aware that it will be Alyson's turn if she wishes. I invite her. Her story, of truncated schooling, work for peace, self-destructive behavior, and gradual recovering, is deeply affecting. The translator meticulously presents her words to Slavko; I am moved by her unwavering professionalism. We explain to him how Alyson lives, the various sources of support for her. When he learns that the government provides much of it, his response is complex and powerful, a mixture of astonishment, anger, and admiration. He is moved almost to tears. Through the translator, he says that at home, the state cares nothing for the individual, that a person with Alyson's problems would have no protection. Here, though, he says, the state seems to care so much for the individual. We hasten to tell him, well, of course, many people do not receive these services. Zan explains several dreadful examples from her work experience. We want so much that he not go home with too rosy a picture. But! I say, The laws are in place, nonetheless, and this is the way it's supposed to be, legally. Whether or not it always works, the intent is there, that individuals shall be taken care of. That is the bottom line. In the USSR, that is not the bottom line, and that's what makes all the difference, and we all know it.

We ask about Slavko's work. But it's still not clear. He works in a factory that makes tv sets, and he is some kind of supervisor who is in charge of maintenance of the factory itself, I think. I tell him how we all were thinking hard of him as he began to come, how we imagined his family and co-workers feting him and sending him on his way with envious good wishes. He tells us how another supervisor, actually his boss I believe, went off to Canada and never came back.

I am interested by his subtle change in demeanor when speaking on his own with the translator. The warmth leaves his face, his tone is harsher in a way. She is a Soviet type of woman, brisk, businesslike, though warm and truly an excellent translator. I see her manner calling up familiar responses in him.

He tells us of the work involved in getting here: the bribes, the three times of coming all the way from Lviv to Moscow and being turned away at the plane to America, the endless infuriating disappointments. We are in awe of his resourcefulness, his determination, his persistence, and the strength of his dream. I tell him, you are Ukrainian in your heart, but American in your mind and spirit.

After everyone has left, he shows us an address and phone number in Framingham; it's clear he needs to do some kind of errand. After some phoning back and forth, it's arranged that we'll drive out there in the early evening. The drive pleases him very much; he has noted all the different kinds of cars, so many Japanese, and he approves heartily of our Toyota. He's especially impressed when we tell him that it is five years old. Of course I let him sit in the front seat. I wish we could let him drive it a little, but I agree with John that that wouldn't be a good idea.

It turns out that the errand is on behalf of Slavko's co-worker at home. He is hoping to emigrate and has given Slavko a letter to deliver to his relatives. The family, a couple and the mother of one of them, live in a lovely house, and although they are pleasant enough, they seem listless. Slavko tells us that they have recently lost their only child to an accident. They address John and me in halting English. We sit at a round table in the kitchen while they speak back and forth with Slavko, in Russian I believe. Slavko delivers the precious message, carried all this way. He is articulate, polite, and very impressive in his manner with these people. I know he is relieved to have done what he promised to do.

Quietly at home again in our kitchen, I word: Homesick? No, well, yes, for Maria and Natalya. Are they jealous? I word. He laughs: Yes, a little. They sending him out like a kite, to see the world from high up, to see over borders, to fly in the illusion of freedom for just a while, then to be reeled in, brought down, but forever changed by that flight.