January 2 - 15 2001 / Antarctica: Sky Water Ice Rock

Seeing the Nacre of the World, as well as the Falkland Islands, a Gateway to the Ice

Part 3 – The Western Side of the Antarctic Penninsula

Late yesterday as we left the eastern side of the peninsula, and the great ice fields, I began to understand about the people who become addicted to it here, to this landscape and the penguins and the ice and snow and colors and forms and seals. I began to have just some withdrawal pain. In the morning when we woke up there was no ice to be seen. I missed the ice, and the pengies--although we do see them now and then in the gray water beside the ship. Ruffles of water slant away from the ship, and the pengies slant away from the ruffles.

Before breakfast we are out on deck, just next to the bridge. From our vantage we can see both the rough brown cliffs of Deception Island, and the narrow ice-filled passage between them, called Neptune’s Bellows, and we can see this on the green radar screen too, and the little dot that is our ship. The captain and his officers gently ease the ship into Whalers Bay through the Bellows. Whalers Bay is a sunken volcanic caldera that is now a fine sheltered bay.

Everyone on deck is admiring the stark cliffs, their every detail limned in snow, so they appear delicate and massive at the same time. We are all taking pictures, the ship eases along past a point when suddenly here is the astonishing sight of some buildings on shore! a masted ship! These incongruities amid the ice draw from every person an exclamation of astonishment, or dismay, or both. We had imagined we were the only humans in this world.

The captain once again drives his ship nearly onto the beach, and we come ashore. All of this is volcanic, the beach is brown and black cinders, and there appear to be some paler fresh cinders, possibly from an underwater explosion, says one of our geologists.

There are jarring juxtapositions here, of human-made objects and structures, and the forms of nature to which our eyes have become accustomed in the past few days. This place was the site of whaling operations in the early twentieth century. There are piles of busted-up barrels, in which whale oil was kept. There are towering rusted tanks in which first fuel and then oil was stored. There are ruins of housing, and what appears to be a laundromat. There is a falling-down hangar where they brought airplanes, for heaven’s sake. There are skeletons of machinery, and whale's bones, partly buried in the shifting blackish cindery beach. There are braided streamlets with mud-colored silt in their beds. All around are implacable white mountains. Death-dealing, impassive, looming over this place which appears, falsely, to be protected: we are told that on our ship’s first trip through here this season, the winds were blowing fifty miles an hour. We have been exceptionally favored in our weather on this whole travel, thus far.

We follow Karen the naturalist, so like me but much more knowledgeable, on a bit of a walk through the cinders and rocks to a vantage point above the water, where we look down on a black beachlet, pintado petrels skimming across the water. They are like big black and white speckled butterflies. They seem to be the only bird here that is not boldly patterned.

It begins to snow lightly and the air and the scene are softened by snow drops. The speckled pintados fly as if behind a scrim curtain.

I return to the black cinder beach to inspect the human relics. There are large wooden dory-like boats half buried in the black sand, with covered decks, used for hauling fresh water out to the ranks of whaling ships that lined this harbor once. There are unidentifiable bits of machinery sticking up out of the sand--gears and spikes and rusted-out containers and even a tractor with tires and seat still in good condition. The enormous storage tanks are covered with big graffiti--1968, 1989, and others I forget.

There is a grave of a Swede, born in 1928 and died in 1971, and a graveyard covered by a mudslide during the recent eruption of 1970. I leave a stone at the grave marker, and meander to the beach.

At the water's edge, among the cindery sand, I notice a kind of dusting on the surface, almost like the dusting of pollen from white pines in spring at home. How very, very far away that is! I scoop some up in my hand. Wonderfully, the handful is dotted with many creatures, all dead—tiny orange-red creatures of various sorts, and two delightful elegantly-sculptured snails, each about an eighth of an inch long. There are tiny strands of algae, pink and green. There are tiny black pebbles. It is a wonder-world, like the inside of a kaleidoscope. I collect handfuls until my hand is too cold to hold them. Just as I start back reluctantly, I see a foot-long creamy strand of something on the black sand. And here is a stick--no, a piece of bone--with which to pick it up. It's an egg mass, of what I don't know, and neither do the naturalists when I get back to the zodiacs.

I show my treasures around to those near me. One lady says, You find such interesting things! I am pleased but embarrassed because the naturalist Karen is standing right there, and she's an expert too at finding neat things. I love dead stuff! she teaches everyone. A woman after my own heart. But although I am pleased I do not wish to be seen in competition, so I say nothing to that fine remark.

I HAVE found a lot of good things. But it's because I look where most other people do not, at the small stuff. And I have a quick imagination, so I make something out of what appears to be nothing to most people.

Back on board, we sail briefly and arrive at another place on Deception Island, called Telephon Bay. There is an excellent hike up to view a sunken caldera. We scramble up through the fresh cinders. There are scattered yellowish boulders with embedded chunks of basalt--this is lithified ash into which bed rock had fallen. At the top of the ridge we are rewarded with a fine view to look down into, and across the pit are beautiful tongues of snow against the brown. Our red parkas glow amid the cinders. We climb up farther, slogging through the loose cinders until we reach the height of land, where everybody takes pictures and admires--admires the handiwork of the Lord, what else can be said of it?

On the way down, John discovers the glacier under the cinders, only a few inches below. We scrape away the cinders, and there is the ice beneath. Even the volcano cannot overcome the Ice.

Now we have anchored briefly at Pendulum Cove, where the hot spring water from within mixes with the cold water of the waves, and people can go "swimming." I did bring my bathing suit, but I don't feel like doing this. So I guess I will pass.

There is a lovely fine snow over everything. It falls at a slight angle, and fills the air with softness. It doesn’t look like snow I have seen before--it is round and soft and amorphous. It is what this continent is made of. It is making this continent. So it is not the transient stuff of home, but rather the very substance of this place.

It seems the place of swimming might be the gateway to Hell. This hell is cold yet steaming, there are rivulets of steaming water gushing through the brown-black sand into the freezing ocean. At the interface, some of our number cavort awkwardly in the water, surrounded by staff who assist, hand out towels, and take pictures. The rest of us observe from the ship (once again Captain Skog has driven his play-toy nearly onto the beach) and cheer them on. It is kind of a silly exercise, but fun to watch.

But after the waders leave, I see this scene for what it is, an interface between the ice and the devil, the ice and the fire within. All around us are cliffs and jagged crags of volcanic stuff, black and darkest brown. This naked geology makes an indifferent landscape, impassive in the extreme. Upon this black beach, the heat of Hell arises through the sand and upon the water, and after we leave, all converges into one funnel of steam and secret violence, veiled now in a pale curtain of snow spicules.

Many are on deck as we pass again through the narrow entrance to this place. I visit the bridge to watch quietly as the captain and his people guide us away (others here, abusing the privilege of the open bridge, are chatting loudly and obscuring the sight of the water). I heard the captain say, Whales dead ahead, and sure enough, there are a couple of humpback whales, leisurely feeding on a krill bloom near the surface, accompanied by many rafts of pintado petrels. Everybody watches this for a while, and then drifts in to tea, incongruously served amid this splendor.

Yet another landing is to be made, this time at Baily Head, on the outer edge of Deception Island. It seems this landing is only made on about one in ten voyages, for there is often a strong swell onto the beach. But conditions have been favorable all along for this trip, and so Matt Drennan, our leader, decides we can land. There are one hundred thousand pairs—one hundred thousand!--of Chinstrap penguins here.

Our landing here is wet indeed, as there is swell and our zodiacs are whooshed onto shore vigorously. It is no more than we have done before in our kayak, though, and so although it is nervy for the staff, and I worry about other, frailer people, I am confident for myself.

We come ashore and leap out of the boat, onto a lovely black beach. There is a penguin highway to the water, line upon line of them coming, going, in endless rows. They must go to sea at this time to bring back fish to feed the chicks that are on their nests. On one side of the beach are layered brown sedimentary rocks, in fantastical spires and curls, and on the other side, all dark volcanic cliffs.

I hear the sound of the feet of thousands of penguins, patting and slapping down the beach and up the beach, in a mindless task of reproduction, to keep the next generation alive. These Chinstrap pengies are perhaps the most appealing and the most curious. They show an almost mammalian curiosity about us. They stand and stare, we stand and stare. I wonder what they see. We see a small, black and white bird with a thin black line under his chin, bright black eyes, pink tough scaly feet, and a black bill.

A valley extends in front of us, and rises up and back as far as we can see. The far side of it is bright green—is this moss, or Prasiola crispa [an alga which thrives where there has been penguin guano]? On the high horizon, perhaps a half mile away or more, we realize there are penguins—there are penguin rookeries, actually, as far as the eye can see! It is easy to see where they are, for instead of gray and black rock, or green algae, there is a faint pinkishness, of krill-filled guano, and amid the pink are thousands and thousands of nesting Chinstrap penguins.

It all begins to come together, finally, for me: between all of these rookeries and the ocean is a penguin highway, crowded with thousands of birds waddling purposefully either toward the water or away from it. Either leaving their chicks to forage for food in the ocean, or returning, perhaps after a week away, their crops filled with partially digested food. They must now waddle or hop laboriously up the cobbly, cindery beach, up the rocks, up the valley, and find the chicks they have left with the other parent, or in the creche. Once the parents have greeted each other, the food is transferred to the chicks, and off goes the other parent, hopping, flopping, padding and plopping down, down down and into the water. The older and bigger the chicks get, the more frequent must be the ocean-going trips. Down and up, down and up, over and over again, hoping to avoid leopard seals each time… I am overwhelmed with anthropomorphic feelings about the patient and stoic heroism of these animal parents.

I am told that the penguins which nest at the highest, farthest regions have an edge, because the snow melts first there. But I am thinking how blade-slender must be their advantage, since they are the ones who must trek and hop and stumble the farthest for their babies’ food.

You can always tell if a penguin at a distance is coming or going, because going he's black and coming he's white. Now that I am at home, sadly, a useless piece of information…

We are able to penetrate a bit into the colony. The smell of course is overpowering (our little cabin on board is quite redolent of penguin). We come up a rise, and there on the hillsides and cliffside ahead, as far as we can see, are more penguins. They must come down to the water from these heights, to go to the ocean to get food for their chicks, at least every week or ten days (that is, they stay at sea for that long, collecting food and feeding themselves), and then as the chicks get bigger and bigger, they must come more and more often. Plop, plop, slap, slap, tumble--down, down they must come, for some of them, a trip of perhaps half a mile, maybe six inches at a hop. And then they must come up again, hop up this rock, hop up the next rock, hop up the next rock, thousands and thousand of hops, until they reach the chicks they have left. The rest of their lives, after the chicks are fledged, they spend at sea, porpoising and leaping in the water, standing or lying on icebergs or ice floes, looking for food and looking out for danger.

The black beach is an endless conveyer belt of penguins, lines going up, lines going down, endlessly in motion. If we are very quiet and stand near them, we can hear the faint pat-pat-pat of their tough little feet.

The crew and staff have worked hard to get us into this landing. There is a big swell at the beach, and people must leap quickly out of the zodiac. Getting back away is much more difficult, and the staff wrestle the zodiac in fair-sized breakers, struggling to control it as it lashes about. Then they've got to get us into it, including some of our folks on canes or with gamy legs. ...the surf surges, the boat writhes, and we jump and scootch, the waves crash into the boat, and off we go.

At the gathering at cocktail hour, we are shown some exquisite images from deep below the surface, from the underwater remote camera. Delicate crinoids, sea stars, sponges and tunicates--all these beneath us. A diver has gone out (wearing forty-five pounds of protective gear, yet only able to stay under for seventeen minutes), and from her footage we see the underside of the pack ice, with its hanging ribbons of algae, food for krill, which are in turn food for nearly everything here, including the giant whales…how fine, how fine. And the feet of icebergs, blue and ghostly and deadly, hanging there in the icy water.

The air is so clear here. Our eyes see each detail as if through some kind of special window.

Oh! I have fallen in love! Again!

People are beginning to talk, in brief conversations, about how they are going to be able to go home. I had not understood before about being addicted to this landscape. But I do understand that now. Yes, I do.

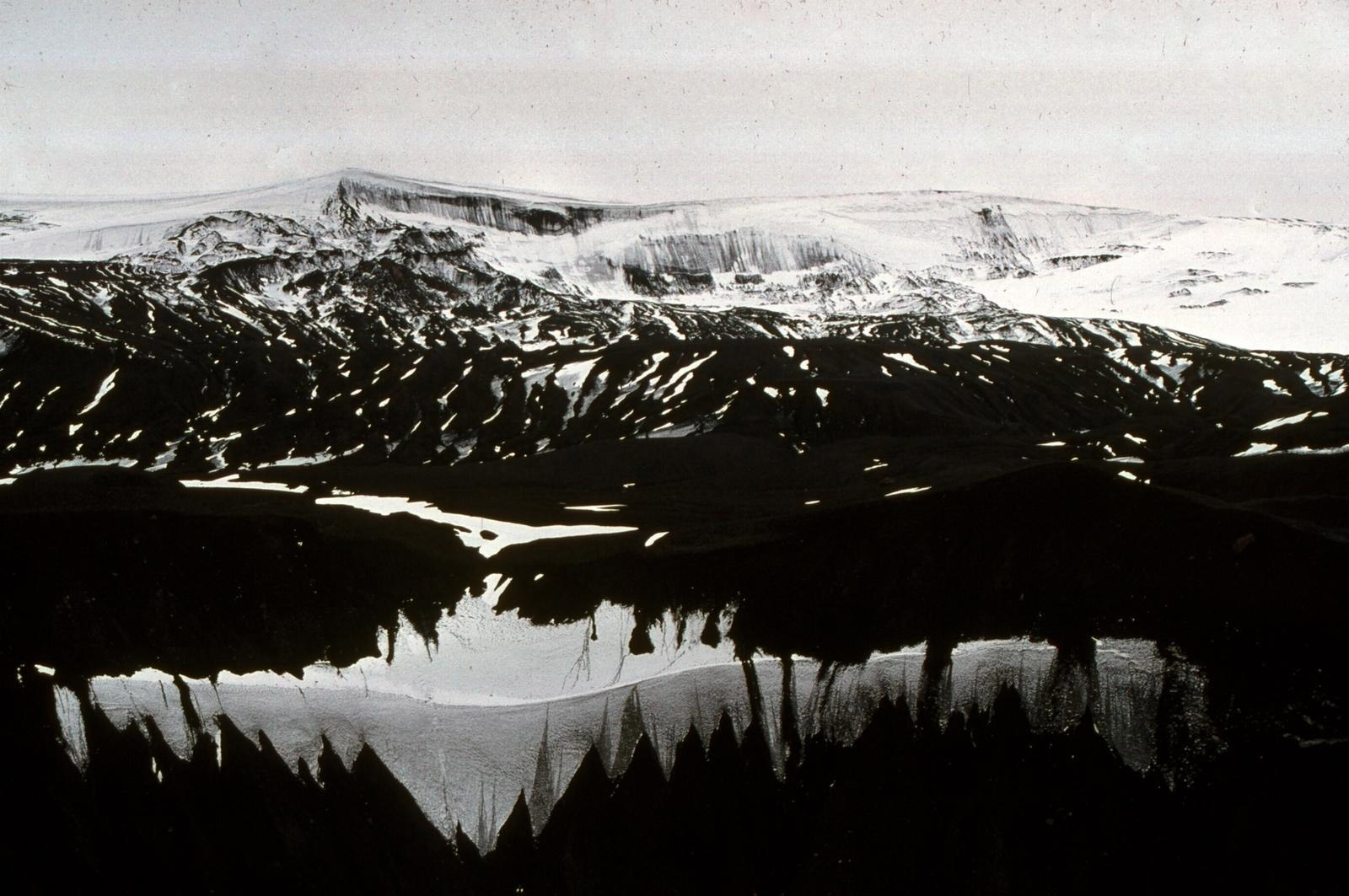

So now we have left Deception Island and returned to the icy waters. We are moving slowly down a narrow passage this morning, called Neumeyer Channel, with dark mountainous peaks heavy with ice and snow on each side. There is fog, and the water is calm and icy black. There is going to be an attempt, in the next few days, to put us below the Antarctic Circle, which is very far south indeed. We shall see, as Captain Skog plays with his big toy.

We got up early this morning, actually there is no morning, since the sun rose at 3 a. m. and will not set on our day. We went out on the deck to see. The channel is lined on both sides by jagged granite peaks which are suffocated with snow, thick suffocating blankets of snow and heavy garments of ice. The ship is going very cautiously for the small bergs and ice cliffs make things harrowing. Our wake creates beautiful patterns of the reflections of snow and stone.

We arrive at a Place. A Place that has people. Port Lockroy, a British outpost that used to be a research station and is now maintained in the summer as a kind of museum, so that we can visit and see how they used to do this. There are two men who stay here summer-long; they sell me an Antarctic patch! The low-ceilinged rooms serve as kitchen, lounge, radio room, bathroom (though only a bath when you bring snow in to melt; whoever brings the snow in gets to take a bath, and they took turns, so if there are nine of you it takes nine days between baths).

There are Gentoo pengies nesting all around. They have chicks, and we take care about them, but they are so used to visitors that they really don't mind us.

The naturalists take part of our group to this Place, and the other part to a tiny rock outcrop just a few yards away, where there are more Gentoos. They have bright orange-red beaks and very pink feet, and they seem quite interested in us, as a mammal might be. In fact, I nearly step on one by accident. I take some pictures of him instead, eating snow. He fills my viewfinder.

There are also the bones of a whale. These are explained nicely to us by one of the naturalists but I prefer not to listen, I just want to look at them, their elegant symmetry and great size and power. Brought down by a puny little group of humans. Upon being told that they'd seen a leopard seal take a penguin on an earlier trip, just here, one vacuous woman says Oh, how terrible! Of course I detest this attitude, but I must say that I do not like the idea of whales being turned into oil, even if it is to read by or to work by.

There is a visitors’ book at the museum. Each ship that comes in--and there have been many I see, most of them Russian-named, probably their ice-breakers--signs under its name and date.

As we sailed away, John and I watched as the anchor was drawn up and up and up, red algae clinging to it, its stout chain making a great clanking noise. When the anchor itself appears, I am awed by its size and wicked shape.

Pretty soon, though, I am on overload, and I tuck in for a nap in the midst of all this glory.

Later, we are at a tiny island, Cuverville Island, and we get to kayak again. Only this time it’s a real paddle; we circumnavigate the little island. There are ice fields all around the inlet in which this island is situated, and at an alarmingly frequent rate we heard the deeply frightening boom of a chunk, a mass, of ice cracking off and thundering into the sea. We come around behind the island and there are marbleized ice fields between great cliffs that tower above our heads. Gulls and terns scream around us. The sea is a bit choppy and we paddle nicely, having left the group that’s hugging the shore. Parts of the cliffs are bright orange with lichen.

The penguins sport about us in the sea; their sounds of splashing accompany us. Their bills are orange and they twitch their tails when they come up, they roll around each other and swim and dive and shoot about in the water. We find them enchanting and it will be hard to leave them. We decide that their mammalian behavior may simply be because they are so large, and they don't fly away from us, but stay and stare at us, the way some small birds do but always at a distance.

On the return half of our kayak trip, of course the wind comes up and some swell, which some of it might be from the calving we hear in the not too far distance, and we paddle through choppy water and bits of swells, and enjoy ourselves keenly, feeling in tune and doing something familiar.

In fact, the kayak trip felt completely comfortable, because it was familiar. But beware!! This is not a place of home. We are now within two degrees of the Antarctic Circle.

We have three more days here, until we must be ready to cross the Drake Passage once again, and begin to withdraw to home. It is very hard to see how we are going to do that, return home.

I am not looking forward to it.